Distributed Energy - What's the goal?

The electric grid is positioned for a major change from its previous centralized model

What is Distributed Energy

At the end of this past summer, our local power utility. Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), held an Innovation Day. During that all-day event they identified the challenges the next generation energy grid will present and the problems the utility will face in making the transition.

They documented 70 problem statements and asked innovators to submit solutions. The problems addressed the electric grid, the natural gas infrastructure, and the new power requirements that electrification poses for previous fossil-fueled energy consumers.

A group of us were particularly interested in the problems that focused on the electric grid and expanded electric use. We decided to develop a solution that addressed a number of the utility’s stated problems.

The focus was on transitioning the electric grid from its existing centralized design instead to a Distributed Energy Resource (DER) design. Now we have to admit that DER is not a new concept. It has been around for many years and most recently has become more important as the cost of solar, wind, and consumer energy storage been drops. This has allowed an increasing number of utility customers to install solar and storage solutions on their buildings. PG&E recognizes this trend and that its future depends on incorporating DER into its product portfolio.

Over the past 10 years we have seen the cost of installed residential solar drop 65% as the cost of the equipment dropped 85%. This has been driven by manufacturing efficiencies that result from increased volumes. We see a similar trend occurring with battery storage. Here both changes in chemistries and the efficiencies of volume production have driven the cost of stationary electric storage down. These rapid changes result from the rapidly growing electric vehicle market where battery sales have been increasing at 12%/year. This trend of cost and price reduction shows little sign of slowing down.

PG&E has a process called Integrated Grid Planning (IGP) that has remained virtually unchanged for the past 40 years in a period of minimal load growth. Power flowed in one direction. Expecting a 70% increase in electric load over the next 20 years, the utility needs to increase capacity while at the same time find ways to deliver on its promise to provide a net zero grid by 2040.

So, what does this mean? It suggests that DER will present a large capacity to augment the electric grid and help utilities achieve their goals.

Why Transition to Distributed Energy

In a previous post about Electrify Everything I had the epiphany that the EVs we have been driving will become the major consumer of electric energy. Granted EVs are much more efficient (about 3X) than fossil-fueled vehicles. But adjusting for the simpler design that the EV offers, that gallon of gasoline still carries about 30 times as much energy as the same weight in batteries. We consume LOT OF ENERGY to run our vehicles.

From my personal example, provided in Electrify Everything, I estimated that we will reduce the amount of energy we consume by 60% as we electrify our transportation and the appliances that provide heat by burning fuel. However, the electric energy replacing those fossil-fueled systems will exceed the electric energy that we use in our buildings today. This suggests that the electric grid will need to handle peaks exceeding two times their current design and that likely the loads will shift in time.

That latter thought, that demand for electric power will shift in time, is significant. During the summer at the beginning of this century the peak load period was late afternoon as air conditioners began to tax the grid. That has changed dramatically today resulting from the rapid adoption of residential and commercial solar. Now the high demand period is shifting to the evening hours. Several times a year, California ISO actually has a surplus of power resulting from the solar, the DER, installations during what used to be the highest demand period.

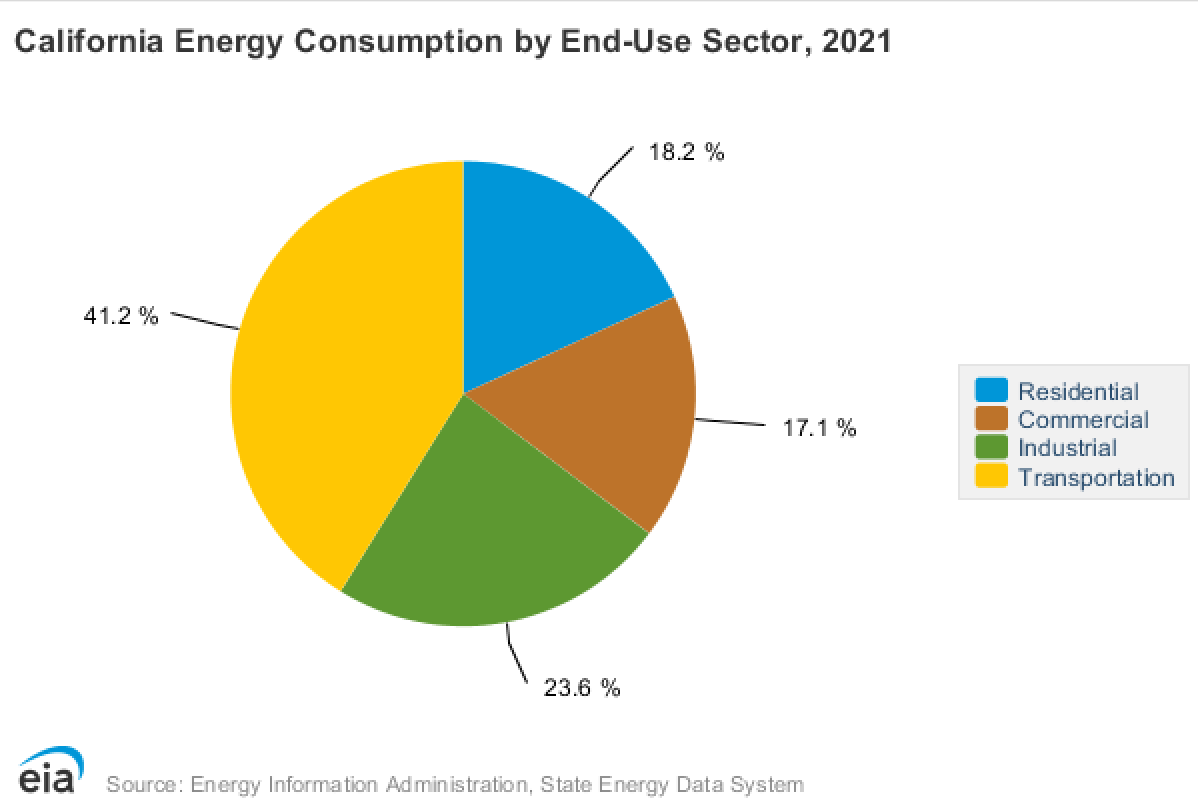

If we look at the pie chart below from the US Energy Institute, we quickly see the impact electrifying our transportation sector will have on the challenges for the electric grid. This is just one of the examples of how the load will shift in time.

Transportation accounts for 41% of our energy demand. Now imagine what the load might look like if we begin fueling our vehicles at home. When a large portion of California’s energy was supplied by nuclear plants which have minimal capacity to change output, there was a surplus of power available after midnight. But today, our most common surpluses are when the sun is brightest. But most vehicles are either in use or parked at work during this time. There is a clear disconnect between the time that energy is available and when it is most needed.

20 years ago, the primary method of storing energy to address the discontinuity between the time when energy supply was available and demand needed it, was by storing water at higher elevations. During periods of excess supply, water was pumped uphill. During periods of excess demand, the water flowed down through generators. This pumped-hydro has the ability to generate 3,960 MW as long as the water lasts. But the peak need in California in 2022 was 52,061 MW., well surpassing that pumped-hydro capacity.

California cars get the best mileage in the nation at 31 mpg. And we sell about 38,000,000 gallons of gasoline per day. That suggests that Californians drive approximately 1,178 million miles a day. If those all are exchanged for EVs getting 4miles/kWh we would need 295,000MWh of electricity delivered each day to fuel vehicles. With the California driver covering and average of 34 miles, it will take almost 5 hours on level 2 for them to recharge. If everyone recharged at the same time, that would demand 58,900MW from the grid. We double our peak as we electrify our travel.

That means we need both twice the supply we have today and twice the transmission capacity (larger wires and transformers) to deliver that electricity than exists today. So the question is not just whether we have the capacity to generate the electricity, but rather do we have a realistic way to deliver it were we to continue to use a centralized model.

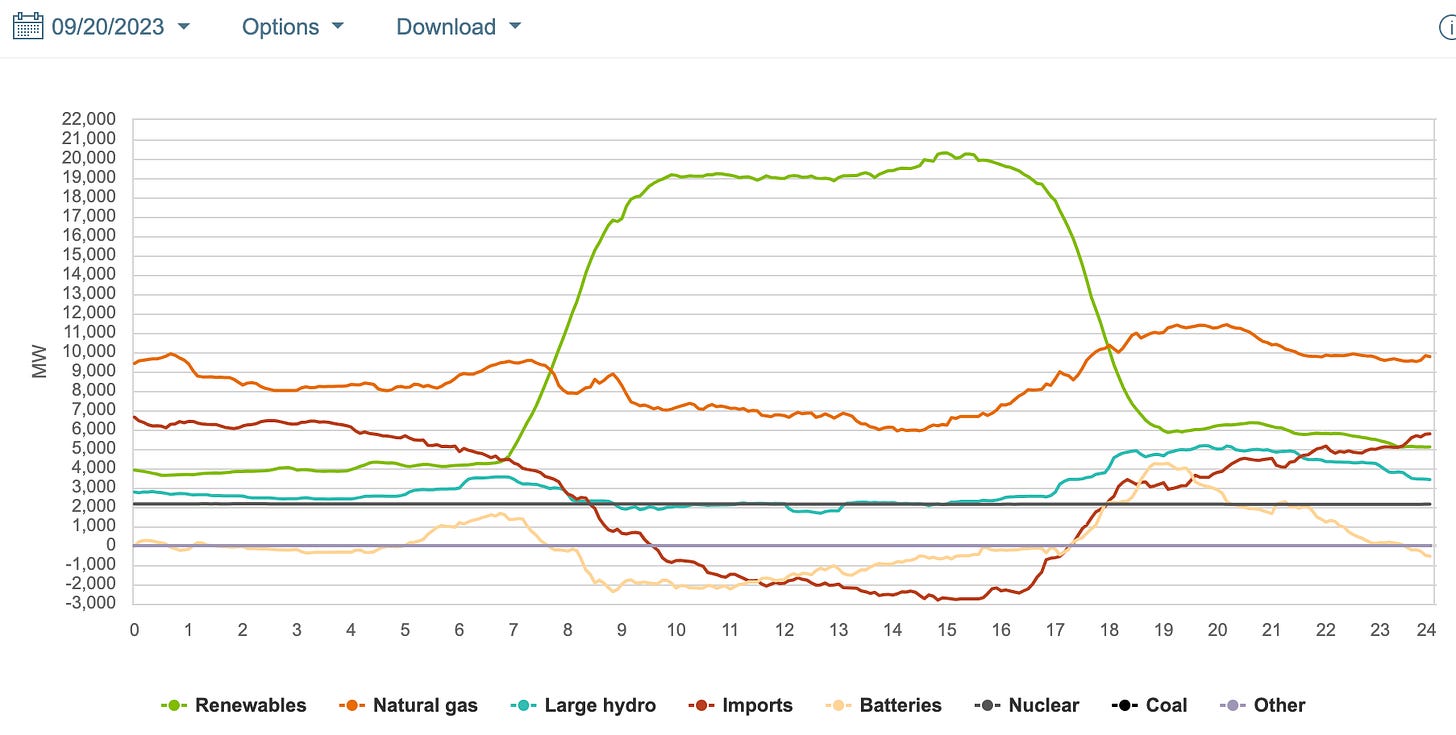

Below, I picked a day this year. Not summer, not winter, but near the equinox to demonstrate the California’s sources of energy.

Renewables today represent the lion’s share of our energy source. But much like nuclear, there is little control over when the supply is generated. With over 17,700MW of renewables in the state, where 15,000MW of it is installed rooftop solar, it is clear this growing DER resource should be both a source of the electric energy we need and a solution to the distribution infrastructure problems.

Looking for a solution to harness DER

In my next post, I plan to describe the Scalablepower SmartStor solution that we submitted to PG&E. It does not focus on expanding solar, but rather how local storage and control of demand can be managed such that it provides benefit to the local user as well as the utility grid.